Before we left for Maine I was looking at a bunch of local tourism and Chamber of Commerce sites, trying to find places to stay and just generally looking at what would be going on while we were there. Aside from sections about accommodations and restaurants and weddings, there was almost always one called something like “Relocate.” Camden’s site featured this little blurb:

Remember the days when neighbors were friends, and your friends ran the local shops and banks? Remember a place where traffic came to a halt for the Soap Box Derby rather than the rush-hour derby? Here where the mountains meet the sea, it’s even better than you remember.

I don’t remember those specific days, to the extent that they ever existed—but I think often about other, more recent ones, and I guess I have equally romantic notions about them. When John and I were walking around that town one afternoon, after salivating over old books and prints and photos and magazines in my favorite kind of rare book shop (where I couldn’t stop myself from buying one amazing issue each of Ladies Home Journal and Better Homes and Gardens from 1954), I was thinking how it’s sort of strange that we ended up on vacation here, and that we even love this place at all. Lots of these coastal towns feel like places for families with young kids, beacons for middle-aged and retired couples (and the occasional young one decked out in pastels) who just want to put their feet up and eat chowder. They’re idyllic in the most obvious and self-conscious ways, even if those ways are genuine ones. The cuteness and kitsch makes me smile, but neither of us would ever think to come here if we didn’t each have a connection with Maine as an idea, a place full of memories that have very little to do with logo sweatshirts, lighthouses, or lobster.

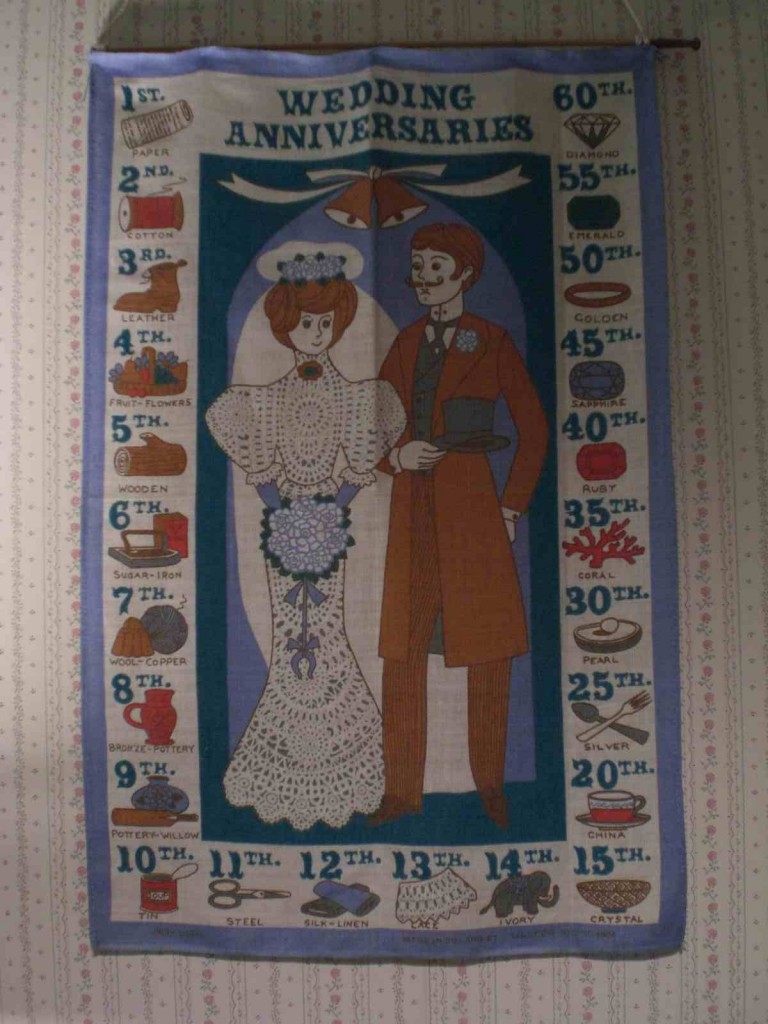

This tea towel was hanging on the wall of our room at a B&B in Belfast (tea towels as wall decorations, enough said). I couldn’t stop staring at it. The first fifteen years of wedding anniversaries are all spelled out with their own symbols, and then there are five year leaps between significant numbers. Who decided on these things, and what was the logic? Why does silk and linen come after steel? Coral after pearl? Wood after leather? Why lump together wool and copper, sugar and iron, pottery and willow, and pottery and bronze? How did they get from lace to ivory in only one move? What is it supposed to mean? There’s probably a charmingly old-fashioned explanation, but hanging at the foot of the bed it felt like a puzzle, and maybe also a taunt.

In Rockport I was fighting the feeling that I needed to make some kind of pilgrimage to the house I lived in for two months, nine summers ago. It seemed possible that I wouldn’t be back to the area any time soon, and it felt sort of necessary to visit that place, the way I did three years ago—just to drive by and notice it, I guess so I’d be able to tell myself I’d been back. I don’t really know why I always think this kind of thing will be reassuring, or even illuminating. Ultimately I decided that driving through town was enough, and that I needed to be okay with not paying a specific visit—that there was nothing there to witness or memorialize that I hadn’t already. That felt like some kind of progress.